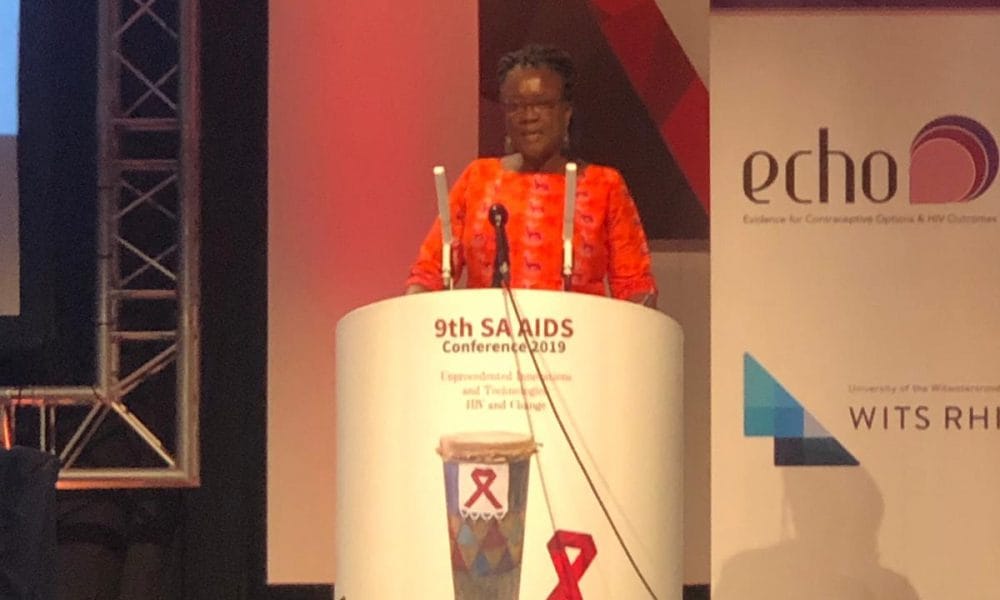

Today at a satellite symposium at the South African AIDS Conference linked to a publication in The Lancet, the ECHO trial of contraceptive use and impact on HIV risk released its results. The Evidence for Contraceptive Options and HIV Outcomes Study, or ECHO, was designed to evaluate the risk of acquiring HIV in HIV-negative women who used the copper-releasing intrauterine device (Cu-IUD), a levonorgestrel (LNG) implant (Jadelle) and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate-intramuscular (DMPA-IM), also known as Depo-Provera.

The topline finding: There was no substantial difference in HIV risk among women using DMPA-IM, the LNG implant or the copper IUD. These are long-awaited data from the most rigorous trial of HIV and contraceptive interactions in history. They are an urgent call to action at a time when women’s reproductive health and rights are under threat in many countries, and the mobilization by and for women’s lives is vibrant and strong.

As AVAC and the women advocates who have led this work in Africa have said in the months and years prior to the result: ECHO must prompt action. Now is the time for investment in woman-centered programs that offer a full range of contraceptive choices and HIV prevention strategies at the same site and in the context of a true informed-choice approach. The ECHO results tell us this is the case. The women who made the trial possible deserve nothing less

ECHO trial did not find any significant difference in HIV risk among women using the three methods studied: DMPA-IM, LNG implant and the copper IUD. Not very many women used pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, for HIV prevention during the trial; women who used DMPA-IM reported more condom use and fewer partners. These choices don’t seem to have made a difference in HIV risk.

All of the contraceptive methods tested were safe, effective and acceptable; the majority of women stayed on the method that they were assigned to use. Very few became pregnant while they were using the method.

There were high HIV incidence rates in all three arms of the trial. This does not mean that the methods increased women’s risk. These incidence rates are comparable to those seen in young women in these countries in other trials and contexts. What is notable, though, is that many trials with comparable incidence rates recruited women with specific HIV risk factors, such as numbers of partners, commercial sex work, sexually transmitted infections, etc. In ECHO, HIV risk factors were not part of enrollment criteria. The participants were sexually active young women looking for contraception. ECHO gives a stark picture of the risk facing these young women. HIV prevention services must meet them where they are—in contraceptive clinics and other related services.

The results are a clear call for contraceptive programs that offer more method choices, including DMPA-IM for women who want to start or continue it, along with comprehensive HIV prevention interventions. The new information from ECHO should be used to improve counseling, expand method choices and rapidly and urgently integrate HIV prevention and treatment with contraceptive programs. The level of HIV risk among eSwatini, Kenyan, South African and Zambian women in the trial was profoundly high. The majority of the participants were under 25, who were not identified as at high risk for HIV—but were simply sexually active and seeking contraception.

The ECHO results are not “good news”. The women in the trial did not have any specific HIV risk criteria. They recruited women who wanted contraception and were sexually active. It is a wake-up call to put HIV prevention on site at every family planning clinic including PrEP and female condoms with peer support, trained providers.

A key question about DMPA-IM has been answered, but that does not mean the method can continue to dominate women’s contraceptive programs in East and Southern Africa. We don’t believe that DMPA-IM should continue to be the only long-acting method available. Black and brown women in East and Southern Africa want choices, dislike side effects and deserve equity with the high-quality contraceptive programs often available in high-income countries.

ECHO shows method mix is possible. Women use many things. Make it happen.

Women need strategies to prevent pregnancies and HIV infection at the same sites, from the same providers, in a rights-based, woman-centered context. Throughout ECHO, the risks of unplanned pregnancy and HIV were pitted against each other by scientists and normative agencies. Now is the time for integration. This has to include investigation—more research on how to deliver services that meet contraceptive and HIV needs well, what is driving HIV risk and how to address it, and more.

The Evidence for Contraceptive Options and HIV Outcomes Study, or ECHO, was designed to evaluate the risk of acquiring HIV in HIV-negative women who used the copper-releasing intrauterine device (Cu-IUD), a levonorgestrel (LNG) implant (Jadelle) and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate-intramuscular (DMPA-IM), also known as Depo-Provera. The trial also compared pregnancy rates among women using these methods, documented rates of method discontinuation and switching, and provides a valuable body of evidence about acceptability of these methods among African women.

Many women1 at risk for HIV are also concerned about avoiding or postponing pregnancy. Some observational studies have suggested that specific injectable contraceptives (e.g., DMPA-IM)2 can increase women’s risk of acquiring HIV, while other studies have not suggested this link between DMPA-IM and HIV risk. Before ECHO, very little was known about other methods and their relationship to HIV risk—no other randomized trial had been conducted on the relationship between HIV risk and a contraceptive method. ECHO was designed to gather high-quality information about how different methods affected risk—whether increasing or possibly decreasing it. One key goal for the trial was to gather information that could be used to shape the WHO classification of and, by extension, the service-delivery approaches for the three methods. In the past years, WHO has used its Medical Eligibility Criteria system for evaluating contraceptives to signal the theoretical possibility that DMPA and similar methods might increase HIV risk. This complex classification hasn’t translated into action in terms of women being informed about risks and benefits, or into procurement of additional alternative methods in most settings. ECHO was also designed to help understand acceptability of methods not widely used in the trial countries.